Bilingualism’s Cry for Attention: how bilingualism can help curb the current wave of nationalism

Mariana Suárez-Rebling Professor Mira Debs EDST 245: Public Schools and Public Policy 05/03/17

Bilingualism’s Cry for Attention

how bilingualism can help curb the current wave of nationalism

Introduction

Am I French? Am I American? Am I Mexican? These are questions that I have been asked by others and asked myself countless times. My parents are Mexican, my sister and I are first generation American and we both attended the Lycée Français de New York. My school was taught entirely in French – other than our daily English class- and allowed students to obtain both American and French High School diplomas. Our school consisted of 1,300 students from pre-k to 12th grade; 30% were French citizens, 30% were French dual citizens, 30% were at least half American and only around 10% had both parents who were from neither the U.S nor France. I was a part of that minority. Everyone wondered why two Mexican parents had decided to send their daughters to a French school, while having no French background or remote knowledge of the language. Why had my parents not simply sent me to an American school?

My parents chose to send me to a school in which only a handful of my classmates knew what the word “integer” meant before SAT prep started Sophomore year. We had done of advanced math but it had all been held in French. None of my French standardized test scores mattered to American colleges, and most of my friends went back to Europe after graduation. I was obligated to take the TOEFL exam. Yet, my parents found these issues trivial compared to the benefits of my bilingual education experience. They valued diversity more than most of our skeptical American family friends did, and rightly so. People seemed to make different assumptions about my nationality based on the environment we were in: I was French-Mexican when with my American friends, Mexican-American in school, Mexican to the Americans and American to the Mexicans. Despite the confusion, I could communicate both verbally and culturally with a much wider variety of people than most of my friends could from a very young age. I learned to embrace diversity in a way that opened my eyes to a very different perspective on the world. But why does this matter today? Many of the anti-globalist problems present in our world today stem from nationalistic and racist views on immigration, inclusion and violence. This wave of nationalism has led to a resurgence of ignorance to the benefits of multiculturalism. Though these problems are in no way easily nor rapidly solvable, a productive step in the right direction is bilingual education.

The History of Bilingualism

In the late seventeenth century in the United States, bilingual education was common practice. When the first colonists were arriving to the United States, most were still teaching their children in their native language, especially Germans. A shift then occurred in the late 1800s: the rise in nativism and large wave of new immigrants at the turn of the century. This shift mixed with the start of World War I led to bilingual education being replaced by efforts to make schools feel more anti-foreign. (8)

In the late twentieth century, many parents, particularly immigrants, were opposed to sending their children to bilingual schools. This stemmed from a stigma against non-assimilated individuals in society. According to a book written in the 1970s by Barry McLaughlin, Second-language acquisition in childhood, “various ethnic groups strive to maintain their identity by raising their children bilingual.” (18) In this case, however, bilingualism means that the child only speaks the non-English language at home, never outside. The book explains that this is due to bilingualism being “a social problem because language is so intimately a part of one’s identity. The distrust shown by many people and governments toward bilingual individuals stems largely from the feeling that they are not loyal citizens because they can speak another language.” (p.2). This belief was developed after a long period of war, which involved the US developing its military more than ever, and segregation. This state of war, increased nationalism and decreased multicultural education. (18)

The combination of these things lead to a nation-wide distrust towards those who weren’t patriotic in every respect including language. As Barry McLaughlin’s book states, “This hostility toward bilingualism has nothing to do with language as such. The hostility is directed not at language but at culture. The bilingual represents an alien way of thinking and alien values” (p.3). This provides insight into the mentality of people in the 70s, whose insights were influenced by nationalism and lack of exposure, leading to racist thoughts. McLaughlin, though unintentionally, also seems to further the idea that being introduced to a different language- and by extension its culture- at a young age produces more open-minded individuals who don’t view the “bilingual” as having an “alien way of thinking” but rather as a person having a different opinion or view. (18)

Benefits of bilingual/bicultural education:

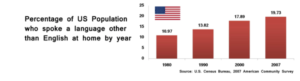

Our world has become significantly smaller thanks to social media. Bilingualism has become increasingly possible with this potential for instant communication. The graph below, taken from “The DANA Foundation” website under the “Cognitive Benefits of Being Bilingual” article published in 2012, shows us that from 1980-2007, there was a substantial increase in the percentage of people in the US who spoke a language that wasn’t English at home. (9)

Today, a larger portion of the world’s population is bilingual or multilingual than monolingual. Research has proven that there are certain benefits that have come up time and time again for kids who learn a second language. Harvard’s associate professor at the Graduate School of Education said that “Bilingualism is an experience that shapes our brain for a lifetime”. The main advantages identified so far include attention, school performance and health benefits. (1)

Attention

People who speak two languages often outperform monolinguals on general measures of academic performance. “[Bilinguals] can pay focused attention without being distracted and also improve in the ability to switch from one task to another,” says Professor Antonella Sorace – a linguistics and english language expert. (9) According to the DANA Foundation, this is due to the cognitive developments that occur, which allow for individuals to “inhibit one language while using another.” (6)

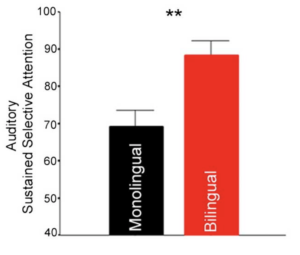

The graph represents the difference between a monolingual and bilingual individual to have sustained attention.

School Performance:

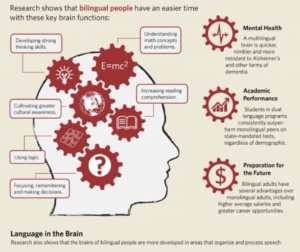

This graph provides visual evidence in favor of the idea that the brain developments that take place due to bilingualism have strong benefits towards one’s academic performance. This is due to the “thinking skills”, mathematical understandings , logic and focus as is demonstrated in the graph. Furthermore, bilingual children, when switching between languages, must follow social cues in order to know which language to speak to whom. This need for accentuated social understanding leads to hyper-developed fundamental social and emotional skills with kids starting at around 3 years old. On top of these social abilities, kids who speak more than one language have been proven to be better English readers than native English speakers due to their puzzle-solving talent. (4) (11)

Health Benefits:

The health benefits of an individual who is bilingual are the most tangible of the advantages. Due to developments in the brain that take place during the learning of a second language, one’s memory is deeply strengthened. This increase in memory, has been proven to delay dementia in patients who have a predisposition to the illness. Doctor’s have found that, though the average age of dementia patients during their first doctor’s appointment is 71.4 years old, that of bilingual patients is 75.8. This might not stop the dementia from occurring but it allows for an incredible delay that provides a longer period of health and normality in a patient’s life. (4), (6), (7)

Policies:

There have been several policies in the past that have tried to establish some momentum in furthering bilingual education. Today, it seems that despite the time that has passed, we may be moving in circles.(12) In 1923, thirty-four states passed laws mandating English as the language of instruction in public schools. This ended any possibility of establishing a curriculum in which English Language Learners (ELL) would be able to learn the core courses in their native languages ( mostly catered towards Spanish speakers), while taking English classes. (14)

In 1963, due to the large number of Cuban immigrants to Miami, elementary schools began offering bilingual education programs for Spanish-speaking students. In the 1970s, states were funding bilingual education programs. Many passed laws allowing schools to teach in languages other than English. (13) (15)

In 1974 the case Lau v. Nichols, a class-action suit brought on behalf of Chinese students from San Francisco, went to the Supreme Court. (16) Most students were not receiving the special instruction that they required due to their inability to speak English. The Court decided that these students “were not receiving equal educational opportunity because they did not understand the language of instruction and the schools were not doing anything to assist them.” (17)

There has never been a mandate requiring bilingual education. The courts and federal legislation–including Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, which “prohibits discrimination on the basis of race, color, or national origin in federally assisted programs and activities”, and the Equal Educational Opportunities Act of 1974, which “defines a denial of educational opportunity as the failure of an educational agency to take appropriate action to overcome language barriers that impede equal participation” are contributors to the progress that has been made in favor of students who are not fluent in English. (4)

Conclusion:

Today, though president Trump hasn’t established specific policies referring to bilingual education, he has spoken extensively about his feelings toward immigrants and his plan to “make America great again”. As his slogan has been analysed time and time again as meaning “make America white again”, there have been predictions that he will not further the pre-existing programs. There have also been concerns about him entirely stopping the ones that already exist. (6)

After researching all of the beneficial aspects of bilingualism, it has become increasingly clear that speaking multiple languages can have positive consequences for everyone, not simply those who speak the languages. Certain benefits identified include strengthened memory, delayed dementia, increased attention span, and academic excellence. However, these are no more important than the more social-based gains, which include cultural understanding, inclusivity and the ability to communicate with a larger group universally.

Due to these social benefits that could occur, the Supreme Court should continue to uphold the rights of non-native English speakers. This should happen for various reasons. FIrst, for the sake of humanity; it must be reminded that regardless of their fluency in English, immigrants are still people and contribute extremely positively to the community. Second, the United States is a country built on immigrants from all continents and backgrounds who unified in order to create a country built on liberty and equality. Third, the United States should make it easier for the motivated, innovative people who chose to move to this country in order to make change. For these creations to take place on US soil is good for the country.

Furthermore, congress should pass a policy to quell these nationalist sentiment by encouraging bilingual education. Education is supposed to enrich an individual both intellectually and socially. Becoming a more well-rounded individual and being more culturally aware are things that will benefit a student far beyond his/her school days. These are things that can create an even smaller world and can allow the violence to lessen. Having gone to a foreign, bilingual school has presented me with the largest diversity of friends, languages and cultures than I could’ve ever imagined. This has created an inclusive nature within me that was developed from the time I was 3 and has kept developing every day since. More kids could develop the same strength.

References:

- Web. <http://www.npr.org/sections/ed/2016/11/29/497943749/6-potential-brain-benefits-of-bilingual-educatio>.

- Web. <http://www.nabe.org>.

- Web. <http://www.npr.org/sections/ed/2016/10/26/498291619/the-return-of-bilingual-education-in-california>.

- Web. <http://www.aft.org/ae/fall2015/goldenberg_wagner>.

- Web. <https://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/1998/05/the-case-against-bilingual-education/305426/>.

- Web. <https://www.ed.gov/news/speeches/importance-bilingual-education>.

, Huffington Post ed.Print.

(9) Web. <http://dana.org/Cerebrum/2012/The_Cognitive_Benefits_of_Being_Bilingual/>.

(10) Academic Press New York San Francisco London. “the Bilingual Child: Research and Analysis of Existing Educational Themes.” (1976)Print.

(11) Afendras. Le Bilinguisme Chez l’enfant.Print.

(12) Carey, S. T. Bilingualism, Biculturalism & Education.Print.

(13) Cohen, Andrew D. A Sociolinguistic Approach to Bilingual Education: Experiments in the American Southwest.Print.

(14) Department of Government Funded Programs and Board of Education of the City of Chicago. “Bilingual- Bicultural Education.” Print.

(15) Educational Testing Service. “Bilingual Education.” Print.

(16) Georgetown University Press, Washington DC. “Current Issues in Bilingual Education.” Print.

(17) Lewis. Bilingualism and Bilingual Education.Print.

(18) McLaughlin, Barry. “Second-LAnguage Acquisition in Childhood.” Print.

(19) Mokhtar Farhadian, Rohani Abdullah, Mariani Mansor, Ma’arof Redzuan, Neda Gazanizadand and Vijay Kumar. Theory of Mind in Bilingual and Monolingual Preschool Children.Print.

(20) Padilla, Raymond V. “Ethnoperspectives in Bilingual Education Research: Theory in Bilingual Education.” Print.

(21) Washburn, David E. “Ethnic Studies Bilingual/bicultural Education and Multicultural Teacher Education in the United States.” Print.

Sex Ed in the Era of Trump: City-Led Reform and Standardization on a Scale that Works

Sex Ed in the Era of Trump: City-Led Reform and Standardization on a Scale that Works

Caroline Francisco / Public Schools & Public Policy / May 2017

Executive Summary

This paper is not intended solely to make the case for comprehensive sexual health education in the United States, nor is it intended as a complete and holistic curriculum proposal; a vast body of research and literature have already established both. Instead, what I hope to explore here is, who should lead the way? Why have some attempts to standardize sex ed been non-effective, and where are more effective policies in place? What political actions can be taken to bring better sex education to American students, and from where should those actions stem? Ultimately, my research suggests two findings. First: that American cities, as mid-levels between school-by-school/teacher-by-teacher action and federal government action, have the most potential to enact effective standardized sex education curricula in schools. I highlight the 2013 implemented in Chicago Public Schools and analyze its effects. Second: that despite a public school system labeled “antiquated,” “failing,” and under fire from the federal government, sex education is a particular area where public schools have potential to excel. (American Federation for Children 2015) (PhilanthropyRoundtable 2013)

Introduction: What is at Stake

Arguing for radical reform of sex education often requires fighting for its existence in the first place. Due to the topic’s charged moralized nature, sex ed has a long history of criticism, especially from religious advocates and those who believe sexual and reproductive conversations belong exclusively in the privacy of the home. Yet in practice, only 43% of parents say they feel “very comfortable” talking to their children about sex, and 50% of teens say they feel uncomfortable talking about sex with their parents. (Planned Parenthood 2011) (Planned Parenthood 2012) Following an incident in Chicago Public Schools (discussed later in this paper’s “Evidence” section), parent Rachel Gigliotti described topics of “sex with a condom, sex without a condom, sex with lube” as “things I wouldn’t even discuss in my own personal life.” (NBC Chicago 2014) If parents are unwilling to discuss fundamental topics like contraception and lubrication in their personal lives, much less with their children, the question is begged: then where, if at all, will young adults learn?

This paper treats education as a public good, and comprehensive sexual education (CSE) as a vital component of that public good. Even differing philosophies of the ‘purpose of education’ offer ample justification for curriculum that includes not only ‘core’ subjects like math and history, but also topics of personal biology, health, safety, risk, and social skills. David Labaree (1997) groups “the root of educational conflicts” into three alternative goals for American education…: democratic equality (schools should focus on preparing citizens), social efficiency (they should focus on training workers), and social mobility (they should prepare individuals to compete for social positions.)” Even though the last goal treats education as a private good, CSE arguably serves all three goals, as its overarching aim is not to encourage premature sexual activities but to empower young people to know the facts, know their rights, and make informed decisions.

Consider the topic of informed consent—when a young person is taught that they equally have the right to say “yes” and the right to say “no,” and a universal right to have their answer honored, they are not only more equipped in sexual situations, but in everyday interactions, in the workplace, legally, and in any situation involving power dynamics. The ripple-effect social implications of this are huge; consider that in 2016, 46% of Americans voted for a candidate well-known for saying, about “beautiful women,” “Grab ’em by the pussy. You can do anything.” (Leip 2016) (NY Times 2016) Would this be the case if every American were educated about consent from a young age? Furthermore, plenty of evidence suggests that good sex education keeps more kids in school longer, to complete the rest of their education: “Nearly one-third of teen girls who have dropped out of high school cite early pregnancy or parenthood as a key reason. Only 40 percent of teen moms finish high school, and less than two percent of teen mothers (those who have a baby before age 18) finish college by age 30.” (Shuger 2012)

The term “comprehensive” sex ed has emerged to distinguish itself from “abstinence-only” sex ed which advises—in many cases morally requires—abstaining from sexual activity until marriage. (By extension, this implies that humans relinquish their right to sexuality if they do not conform to social constructs of marriage.) Abstinence-only education is historically ridden with value judgments against sexually active individuals and double standards against women. In various abstinence-only curricula around the country, a woman who has lost her virginity before marriage is likened to a dirty sneaker, a chewed stick of gum, a used piece of tape, or a piece of chocolate that has been passed around the class: used, dirty, undesirable, and worthless. (LastWeekTonight 2015) (Semuels 2014) This sends messages to young girls that they exist to marry and be valuable to men, that sexual activity devalues them, that “they cannot be sexual beings in the way that boys can,” and for female victims of sexual assault, that the fault is theirs. (Beyoncé 2014)

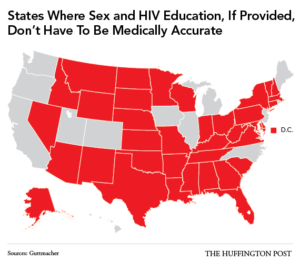

Is this kind of education the norm or the outlier? What does sex ed look like in most American public schools? A proper diagnosis is elusive; despite the growing trend towards accountability measures in core subjects, almost no accountability or effective standardization exists for sex ed. Research shows however that even in 2017, sex ed in America looks more like the “chewed stick of gum” model than not. Guttmacher Institute, which provides the leading data on sex ed standards, reports that as of May 1, 2017, only 24 states and Washington DC mandate sex education, and only 13 require that the information presented be “medically accurate.” 37 states require that when sex ed is offered, abstinence be either “stressed” (26) or “covered” (11), while only 18 states require offering information on contraceptives. Only 2 states explicitly prohibit sex ed programs from promoting religion, and in 3 states—Alabama, South Carolina, and Texas—any information presented on non-hetero sexual orientation must be explicitly negative. Furthermore, countless schools rely on outsourced curriculum materials—public or private—to show in their classrooms, which means that variance from school to school is almost impossible to track. Some kids are getting Planned Parenthood representatives in class, some kids are getting condom-on-banana demonstrations in class, some kids are getting the chewed gum analogy, some kids are getting a lady John Oliver describes as “trying to yell the horniness out of teenagers,” some kids are getting exhaustive lists of sexually transmitted diseases without ever being taught what sex is or how it works or why humans have it in the first place. (LastWeekTonight 2015) Some kids are getting nothing at all.

Figure 1. Map from the Huffington Post via Guttmacher Institute. (Klein 2014)

What are we trying to prevent? Are we trying to prevent students having sex? Or are we trying to prevent early pregnancy, sexually transmitted diseases, sexual assault, and unhealthy sexual relationships? Abstinence-only education leans on the former even if under the guise of the latter. And while there is a strong philosophical case to be made that only the latter deserves a place in public education, extensive research shows that abstinence-only education is already failing at both. In 2014, the same Mississippi town that used the dirty chocolate classroom lesson reported that 76% of teenagers are sexually active while in high school, and that the local birthrate was 73 out of 1,000 females between 15 and 19: nearly triple the national rate at the time, which while declining, is still among the highest in the developed world. (Semuels 2014) (Holpuch 2016)

By contrast, a “comprehensive” sex education is set apart not only by medical accuracy but by inclusivity. While abstinence is technically medically accurate (yes, it is the only 100% effective way to prevent pregnancy and STIs), it omits much of the larger picture: the normalcy of sexuality in development, informed consent, contraceptive methods (especially those beyond the male condom), abortion, sexual pleasure, masturbation, forms of attraction, gender identity, sexual orientation, healthy relationships, and more. (Advocacy for Youth)

Ironically, the crux of the dilemma is that while CSE programs are elusive, support for them isn’t. National endorsement of CSE is overwhelming, not only among medical, scientific, and public health professionals, but also among education authorities, and even the American public. (SIECUS) So why is CSE so difficult to implement? The next sections explore attempts to enact and enforce CSE on various scales, and where this has been most effective.

Background: Attempts at Standardization

A 2015 editorial by Alice Dreger—writer, medical historian, bioethicist, and parent of a high-school boy—asked “Why isn’t sex education a part of Common Core?” Her question raises a confusing trend in national accountability: Common Core has embodied the huge push in national curriculum standardization, yet it only accounts for math and language, leaving other subjects relatively untouched. In some cases, Common Core’s emphasis on these two subjects has even had adverse effects on other subjects: in schools where standardized math/ELA test scores are low and budgets are increasingly skimpy, ‘non-core’ programs such as art, music, technology, physical education, vocational education, and health are often first on the chopping block to accommodate more time, money, and resources towards raising scores. In her article, Dreger advocates for consent and pleasure education to replace time spent on “endless lessons about how to put on a condom,” apparently not realizing how many American students won’t get condom education at all, much less consent or pleasure education. Oddly enough, she addresses the disparities in American sex ed twofold, both explicitly in her call for national standards, and implicitly in her ignorance of ‘how bad some other kids have it.’ (Dreger also gained media attention later that year for live-tweeting her son’s East Lansing, MI sex ed class, which featured abstinence-only speakers connected with a local anti-abortion “crisis pregnancy center.” (MLive 2015) The awareness she raised eventually pushed the school board to pull the religiously-affiliated speakers from their curriculum. (Culp-Ressler 2015))

Ultimately, Dreger’s article does more to advocate for why CSE should be nationally standardized than explain why it is not already. To answer this question, it’s necessary to delve into the history of sex ed standardization attempts, and examine the stark contrast between the drivers of Common Core and the drivers of nationalized CSE.

Though not remotely affiliated with Common Core, national sex education standards do exist, and they are comprehensive. “The National Sexuality Education Standards: Core Content and Skills, K-12” were released in 2012 by the Future of Sex Education (FoSE) Initiative, a “partnership between Advocates for Youth, Answer, and the Sexuality Information and Education Council of the U.S. (SIECUS).” They differ from Common Core in several key ways.

- Curriculum and tools for teachers are free, online, and open-sourced. FoSE’s website provides not only a detailed list of the standards for each grade, but a long list of tools for implementation that hone in on training teachers and other personnel (nurses, psychologists, etc.) and supplying administrators with templates to assist and evaluate budding CSE programs in their schools. (FoSE 2012) These tools are available to any teacher or school who wishes to access them, yet they require bottom-up self-implementation and enforcement. FoSE does not explicitly provide funding or personnel for teacher training, only written materials. By contrast, Common Core is implemented top-down in schools and classrooms. Teacher participation is mandatory, and both teacher and student performance is evaluated by national tests that the state has adapted.

- The stakes and accountability are different. Because of the personal and social nature of sexual education, it’s harder to track successful implementation in the same way. A math test generally gives a pretty good sense of what math a student knows and how they will use it in the real world. A sex education test, even if it measured what a student knew, wouldn’t necessarily provide any insight into how that student would make decisions in the future. (Given some of the abstinence-only programs we examined previously, it wouldn’t take a genius to figure out ‘sex is bad, don’t have it’ is they key to a high score on a test in an abstinence-only school.) While the stakes of both are high, sex education is more about social skills and personal health than competition and employability.

- The National Sexuality Education Standards were created by non-profits. These standards are crafted to be national but have no explicit federal government ties or endorsements. By contrast, Common Core is written by a coalition of states and incentivized as part of Obama’s federal Race to the Top program, and is surrounded by a wide support web (funding, public relations, content contributions) of state governments, third party companies, and prominent individuals. (Bernd 2013)

These three key differences shed light on the most important difference between NSES and Common Core, namely that the latter has been widely adopted by states, and the former hasn’t: unlike Common Core, states have essentially no tangible incentive—that is, financial incentive—to adopt NSES. While Common Core is tied to a bundle of federal carrots including Race to the Top grants and Title I funding for struggling schools, the non-profits that created NSES cannot fund the implementation of CSE standards, much less fund rewards for implementing CSE standards. (Kertscher 2013) (Ravitch 2016)

It’s no secret that the current federal administration’s views on public schooling, women’s rights, public health, gender, and sexuality make for a bleak outlook for federally-incentivized CSE; an administration that recently attempted to revoke transgender students’ Title IX protections in public schools is highly unlikely to support CSE that includes discussion of sexuality and gender identity in the first place. (Peters et al. 2017) There are some arguments to be made for how nonprofit coalitions like FoSE could incentivize implementation: perhaps by reorganizing spending to offer aid to districts implementing CSE, or to broaden their coalitions (maybe to include for-profit allies) to increase funds and support, or to emphasize how CSE could ultimately lower costs for states and schools (decreases in teen pregnancy and STIs could potentially lessen government funds spent on public assistance and state-subsidized health services.) However, perhaps in the name of efficacy, national standardization isn’t the necessary route at all: the next section will explore the pros and cons of alternatives.

Evidence: City-Based Public CSE Projects, Chicago as a Model

We find ourselves in search of a middle ground: good sex ed is so important that it can’t depend solely on the luck of a good teacher (a fictional 2014 movie popularized this narrative, placing a virginal straight white male teacher in a majority Latinx school to ‘save’ their sex ed program) but there’s also evidence to suggest that federally and nationally implemented standardization is neither probable, enforceable, nor measurably effective. City-led CSE reform just might be the middle ground that is needed to balance some level of large-scale standardization with small-scale implementation.

Chicago Public Schools (CPS), the third largest public school district in the continental US, has led the way in forging CSE reform at the city level. The Chicago Board of Education effectively implemented NSES in CPS in February 2013, with no clear catalysts or financial incentives at the time. (CPS Policy Manual 2013) By May 2013, House Bill 2675 mandating “medically accurate, developmentally and age-appropriate” Comprehensive Health Education was passed by the Illinois General Assembly, and eventually signed into law by Governor Quinn; prior to this, Illinois had not mandated teaching sex education at all, and when provided, mandated medical and moralized stress on abstinence. (NCSL 2016) By June 2013, the Chicago Dept. of Public Health (CDPH) published a policy brief in support of the recent city and state reforms, lending its support to the CPS CSE rollout and announcing a federal Teen Outreach Program (TOP) grant jointly awarded to CDPH and CPS for their cooperation in reducing teen pregnancy.

Chicago is a remarkable case study for several reasons. First: Chicago is a rare example of where NSES standards and trainings have been explicitly adopted in actual classrooms. Second: this reform occurred at a time when the federal government was in fact increasing spending for abstinence-until-marriage programs by $75 million a year. (de Melker 2015) Third, and most importantly: although Chicago’s CSE initiative eventually received state and federal reinforcements (both legally and financially), this reform was city and district-led. Only after the district policies were enacted did state law and federal dollars follow suit.

Chicago’s road to CSE reform hasn’t been an entirely smooth one; it hit its most public snafu in November 2014, after parents encountered material that detailed “the basics of female condoms,” “feel-good reasons to use them,” and “other forms of contraception, sex toys and sex acts” in CSE curriculum materials for fifth and sixth graders. CPS responded with, “The objectionable material presented at Andrew Jackson Language Academy this week is not and never was part of the student sexual education curriculum. It was mistakenly downloaded and included in the parent presentation, and we agree with parents it is not appropriate for elementary school students.” (NBC Chicago 2014) Indeed, most parents involved in the controversy supported CPS’ CSE reforms, but were largely concerned with the age-appropriate timing of material rather than CSE itself.

Improvement of the initiative may require some ‘tinkering towards utopia’ (to use a choice phrase in educational reform), but on the whole, response has been positive. In December 2014, CPS Sexual Health Program Assistant Maalika Bannerjee wrote: “Though there are hiccups, and progress can take time, it’s happening. Even I, coming from a liberal school in Massachusetts, didn’t have a chance to discuss gender identity or consent or healthy decision making in the classroom. By 2015, students in over 600 CPS schools will be able to do just that.” In distinct difference from the mistaken material, her accounts detailed activities that were far more commonplace in CPS schools as a result of the rollouts: for instance, a teacher-training exercise where participants had to describe their weekend without using gendered language. Bannerjee writes,

“There’s a pause. I notice some teachers begin sentences, and then stop. But after a few minutes, the conversations begin to flow. At the end, I ask them how it went. One gym teacher said he struggled with the activity. ‘I said ‘I’ a lot, and it felt really impersonal,” he said. Another person chimed in with some alternatives; he suggested the use of “they” in place of “he” or “she,” and “partner” or “significant other” in place of “boyfriend” or “girlfriend.” Another teacher said the activity helped her think about how difficult it is for some LGBTQ students, who may need to revise their language in school to avoid harassment from their peers. And yet another person said it made him think about using more inclusive language in the classroom, to make all students feel safe and comfortable at school.” (Bannerjee 2014)

Although Chicago’s 2015 Youth Risk Behavior Survey (YRBS) data is not yet available to compare with 2013 data and gauge rollout effects, CPS has seen tangible positive impacts of the reforms in other ways. Some take the form of the classroom interactions like the one Bannerjee recorded above. Others take the form of student activism in the wider Chicago community. In December 2015, the Chicago Tribune reported on a 17-year-old CPS high schooler, Heaven Johnson, who partnered with the city’s Public Health Department to “launch a citywide safe-sex initiative that includes posters at CTA [metro] hubs and other parts of the city, a social media campaign (#ChicagoWearsCondoms) and volunteers periodically handing out free condoms.” Johnson’s efforts are quite literally seen all over the city, and her website directs citizens to “169 locations around Chicago that distribute free condoms, as well as addresses, phone numbers and hours for facilities that provide free sexually transmitted infection and HIV testing and treatment.” (Stevens 2015)

Figure 2. Photo from CPS high-schooler Heaven Johnson’s Chicago Wears Condoms Campaign. (Stevens 2015)

Conclusion

As with any policy model, city-led CSE reform is not proposed as a catch-all panacea to rescue America from sex ed’s victimization at the state and federal level. Some locations prove more difficult than others: for instance, in New Orleans, city-led CSE proposals faced similar roadblocks and backlash from the state level as state-led CSE proposals. (O’Donoghue 2015) Some locations don’t have the luxury of a school board large enough to encompass many schools nor formidable enough to spar with conservative municipal governments: persistent advocacy is still needed at the state level, especially to make sure rural students don’t ‘fall through the cracks’ of CSE reform.

However, I present the Chicago model as an exciting case where national CSE standards are actually starting to reach classrooms and have a positive impact on students as a result of localized bottom-up action. Despite initial state and federal resistance, Chicago’s great strides in CSE represent not only the potential of American cities, but indeed of public schools.

[Word Count: 3469]

Acknowledgments

Special thanks to peer editors Eliza Scruton and Molly Ono.

Works Cited

Advocates for Youth. Sex Education Programs: Definitions & Point-by-Point Comparison. Retrieved from http://www.advocatesforyouth.org/publications/publications-a-z/655-sex-education-programs-definitions-and-point-by-point-comparison

American Federation for Children. (2015, March 13.) Betsy DeVos SXSWedu. [Video file.] Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=f_2nH4aLLDc&feature=youtu.be

Bannerjee, M. (2014, December 30.) Taking Pride in Progress: Implementing Sex Ed in Chicago. Retrieved from http://nhc.networkforchange.org/chicago/blog/taking-pride-progress-implementing-sex-ed-chicago

Bernd, C. (2013, September 6.) Flow Chart Exposes Common Core’s Myriad Corporate Connections. Retrieved from http://www.truth-out.org/news/item/18442-flow-chart-exposes-common-cores-myriad-corporate-connections

beyonceVEVO. (2014, November 24) Beyoncé – ***Flawless ft. Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie. [Video file.] Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=IyuUWOnS9BY

Chicago Department of Public Health. (2013, June.) SEXUAL EDUCATION POLICY IN ILLINOIS AND CHICAGO. Retrieved from https://www.cityofchicago.org/content/dam/city/depts/cdph/CDPH/HCPolicyBriefJune2013.pdf

Chicago Public Schools Policy Manual. (2013, February 27.) Title: SEXUAL HEALTH EDUCATION; Section: 704.6; Board Report: 13-0227-PO1. Retrieved from http://policy.cps.edu/download.aspx?ID=57

Culp-Ressler, T. (2015, April 21.) One Woman Live-Tweeted Her Son’s Abstinence-Focused Sex Ed Class. Now Things Might Change. Retrieved from https://thinkprogress.org/one-woman-live-tweeted-her-sons-abstinence-focused-sex-ed-class-now-things-might-change-415fdd10b6e6

de Melker, S. (2015, May 27.) The case for starting sex education in kindergarten. Retrieved from http://www.pbs.org/newshour/updates/spring-fever/

Dreger, A. (2015, February 27.) Why Isn’t Sex Education a Part of Common Core? Retrieved from https://psmag.com/why-isn-t-sex-education-a-part-of-common-core-4a5b1a4deb7f

FoSE. (2012.) National Sexuality Education Standards. Retrieved from http://www.futureofsexed.org/nationalstandards.html

FoSE. (2012.) The National Teacher Preparation Standards for Sexuality Education: Tools for Implementation. Retrieved from http://www.futureofsexed.org/implementation.html

Guttmacher Institute. (2017, May 1.) Sex and HIV Education. Retrieved from https://www.guttmacher.org/state-policy/explore/sex-and-hiv-education

Holpuch, A. (2016, September 28.) US teenage birth rates fall again but still among highest in developed world. Retrieved from https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2016/sep/28/us-teenage-birth-rates-fall-again

Kertscher, T. (2013, October 24.) How much is the federal government involved in the Common Core school standards? Retrieved from http://www.politifact.com/wisconsin/statements/2013/oct/24/sondy-pope/how-much-federal-government-involved-common-core-s/

Klein, R. (2014, April 8.) These Maps Show Where Kids In America Get Terrifying Sex Ed. Retrieved from http://www.huffingtonpost.com/2014/04/08/sex-education-requirement-maps_n_5111835.html

Labaree, D. (1997.) Public Goods, Private Goods: The American Struggle over Educational Goals. American Educational Research Journal 34(1):39-81.

LastWeekTonight. (2015, August 9.) Sex Education: Last Week Tonight with John Oliver (HBO). [Video file.] Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=L0jQz6jqQS0&pbjreload=10

Leip, D. (2016.) 2016 Presidential General Election Results. Retrieved from http://uselectionatlas.org/RESULTS/national.php

MLive. (2015.) Author tweets sex ed course at East Lansing school. Retrieved from https://storify.com/MLive/author-tweets-sex-ed-course-at-east-lansing-school

Moviclips Trailers. (2014, October 11.) Sex Ed Official Trailer #1 (2014) – Haley Joel Osment Movie HD. [Video file.] Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=j2vmzw9GjEo

National Conference of State Legislatures. (2016, December 21.) STATE POLICIES ON SEX EDUCATION IN SCHOOLS. Retrieved from http://www.ncsl.org/research/health/state-policies-on-sex-education-in-schools.aspx

NBC Chicago. (2014, November 14.) Parents Shocked by Material in Presentation on School’s New Sex Health Curriculum. Retrieved from http://www.nbcchicago.com/news/local/Parents-Shocked-by-Material-Mistakenly-Included-in-Presentation-on-Schools-New-Sex-Health-Curriculum-282788211.html

The New York Times. (2016, October 8.) Transcript: Donald Trump’s Taped Comments About Women. Retrieved from https://www.nytimes.com/2016/10/08/us/donald-trump-tape-transcript.html?_r=0

O’Donoghue, J. (2015, May 19.) New Orleans doesn’t get the sex education curriculum it wants. Retrieved from http://www.nola.com/politics/index.ssf/2015/05/new_orleans_sex_education_abst.html

Peters, J., Becker, J., & Hirschfield Davis, J. (2017, February 22.) Trump Rescinds Rules on Bathrooms for Transgender Students. Retrieved from https://www.nytimes.com/2017/02/22/us/politics/devos-sessions-transgender-students-rights.html

PhilanthropyRoundtable. (2013, Spring.) Interview with Betsy DeVos, the Reformer. Retrieved from http://www.philanthropyroundtable.org/topic/excellence_in_philanthropy/interview_with_betsy_devos

Planned Parenthood Federation of America. (2011, October 3.) New Poll: Parents are Talking With Their Kids About Sex but Often Not Tackling Harder Issues. Retrieved from https://www.plannedparenthood.org/about-us/newsroom/press-releases/new-poll-parents-talking-their-kids-about-sex-often-not-tackling-harder-issues

Planned Parenthood Federation of America. (2012, October 2.) Half of All Teens Feel Uncomfortable Talking to Their Parents About Sex While Only 19 Percent of Parents Feel the Same, New Survey Shows. Retrieved form https://www.plannedparenthood.org/about-us/newsroom/press-releases/half-all-teens-feel-uncomfortable-talking-their-parents-about-sex-while-only-19-percent-parents

Ravitch, D. (2016, January 22.) EXCLUSIVE: How Does ESSA Affect Opt Outs? Part 4. Retrieved from https://dianeravitch.net/2016/01/22/exclusive-what-does-essa-affect-opt-outs/

Semuels, A. (2014, April 2.) Sex education stumbles in Mississippi. Retrieved from http://www.latimes.com/nation/la-na-ms-teen-pregnancy-20140403-story.html

Shuger, L. (2012.) Teen Pregnancy & High School Dropout. Retrieved from https://www.americaspromise.org/sites/default/files/legacy/bodyfiles/teen-pregnancy-and-hs-dropout-print.pdf

SIECUS. Who Supports Comprehensive Sexuality Education? Retrieved from http://www.siecus.org/index.cfm?fuseaction=Page.ViewPage&PageID=1198

Stevens, H. (2015, December 3.) Chicago (and its skyscrapers) wear condoms, thanks to new campaign. Retrieved from http://www.chicagotribune.com/lifestyles/stevens/ct-chicago-wears-condoms-campaign-balancing-20151203-column.html

Fighting for a Future: The Massachusetts ‘No on 2’ Campaign and Its Impact on Public Education Advocacy

Daniel Vernick, May 2017

Fighting for a Future: The Massachusetts ‘No on 2’ Campaign and Its Impact on Public Education Advocacy

Executive Summary

The efforts of the Massachusetts Teachers Association (MTA), the main teacher union in MA and the central organizer of the 2016 anti-charter campaign, were instrumental to the success of the No on question 2 campaign. The campaign was a success due to its grassroots field operation, effective messaging, and community-based support, and can serve as a model for the public education movement in Massachusetts and across the country.

Introduction

In 2009, the MTA compromised on a deal in the MA legislature to raise the cap on charter schools. They did so because if the bill failed, it would go to a ballot measure – and, in a national atmosphere in which support for charters was rising among both Republicans and Democrats as well as championed by the Obama administration, the union leaders were convinced that such a ballot measure would pass and leave lasting damage on Massachusetts’ public schools. This changed with the election of Barbara Madeloni as MTA President. Madeloni believed in an forcefully progressive approach, a strategy that ended up working. Fast forward to 2016, and Madeloni decided to embrace the anti-charter campaign. According to the polls, which showed a landslide victory for the pro-charter side, many said she should invest union resources elsewhere. Question 2 ended up being defeated 62-38. The result was not only a landslide in public support away from charters but also a landslide of questions for pro-charter advocates, whose strategies largely failed. The result rejuvenated public education advocates and provides a route of resistance against the charter lobby that once seemed too powerful to resist, which is particularly relevant in the Trump-DeVos era.

Background

When Madeloni was elected, the MA legislature in 2014 was again about to raise the charter cap. Madeloni “urged her rank and file” to resist lifting the cap, which succeeded and showed the potential for grassroots organizing among public education advocates. The potential for a referendum was viewed as negotiating tool by the pro-charter side because it would allow for such a dramatic expansion in charters.[1] MA State Senate ended up passing the Rise Act, which tied charter cap increases to an increase in local education funding for 7 years and would cost 203-212 million per year.[2] The House decided not to compromise with the Senate on the bill and instead leave charters up to the voters, setting off the 2016 ballot campaign.

Madeloni’s willingness to take such a controversial issue head-on and success at mobilizing her membership was crucial. The result was that “teachers came out in force to talk to their neighbors,” and most people place high trust in teachers. One teacher said that their “neighbors looked to [teachers] as authorities on the issues involved in the ballot question, and greeted them warmly when approached to discuss” the anti-charter campaign[3] – a starkly different reaction than most political canvassers receive.

There are currently 78 charters in MA.[4] The current charter cap allows for 120, with 4-5 approved each year. The cap also includes a limit on the percentage of school budget spent on charters, preventing districts from spending more than 9% of their budget–and 18% in low-performing districts–on charters. In cities such as Boston, Lowell, and Springfield, the financial limit has resulted in waiting lists. In 2010, a “smart cap” was instituted. This prioritizes charter applications from CMOs “with a proven track record that seek to expand in low-performing districts.” Still, the charter cap has limited charters in many cities, with tens of thousands of students on waitlists.[5] Question 2 would allow an additional 12 charters per year for an unlimited number of years.

Top in the Nation: Massachusetts Charter Schools

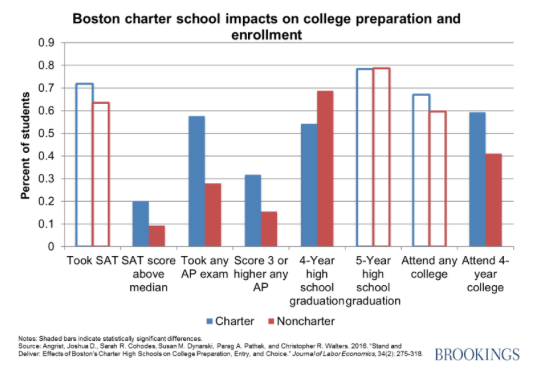

The pro-charter campaign centered on the fact that MA charters are some of the highest performing in the nation and have avoided the scandals than plauge those in other states. A recent Brookings report claims that MA urban charters have positive student outcomes and increase the performance of low-performing students. The MA charter application process “is one of the most rigorous in the country,” which is shown by the closure of 17 charter schools “deemed ineffective or mismanaged” since 1997.[6]

DESE reviews all applications for MA charters. This centralized system allows for universal standards to hold charters accountable and is starkly different from other states, allowing for high performance.[7] Attending a Boston charter for one year results in a substantial increase in test performance and eliminates 1/3 of the “racial achievement gap.”[8] Competition among charters is part of the reason why MA charters are high-performing, and therefore the anti-charter side argued that drastically decreasing competition would have negative effects on charter quality.

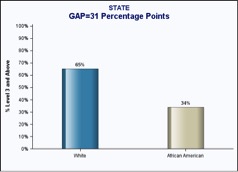

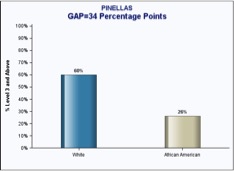

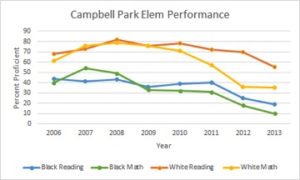

Figure 1

Figure 2

“Great Schools” or “Save Our Public Schools”: Campaign Messaging and Arguments

Charter supporters planned a three part strategy. First was the legislative effort, then a ballot question, and the third alternative was a lawsuit using an elite Boston law firm to “file a class-action suit to lift the charter cap” because “it unconstitutionally denies children access to an adequate education.”[9] Great Schools MA was the umbrella pro-charter campaign committee. Families for Excellent Schools (FES) was the primary organization under the umbrella. FES is a “powerful pro-charter force in NYC,” and opened a branch in MA solely to lobby for question 2. FES is funded by Wall Street donors, many of whom would benefit financially from increased charters. It claims to be grassroots and parent-based, but the reality is that “a small group of charter school chains, politically connected Wall Street financiers, and powerful education officials have controlled FES since its founding.”[10] In New York, FES organized public displays of pro-charter activism, such as 30,000 people marching across the Brooklyn Bridge; “theirs is a powerful spectacle, until one looks too closely and notices that the guys on the walkie talkies are all white and that the parents were told that they had to attend.”[11] MA Secretary of Education James Peyser was on the board of FES as well as a “managing partner of New School Venture Fund,” which is “among the first and largest investors in charter schools and the first to support multi-site” CMOs. Therefore he had a direct interest in passing question 2. Furthermore, as Executive Director of the Pioneer Institute, Peyser also “helped craft a strategy for the charter expansion forces” in MA.[12] FES failed due to its vague messaging that shied away from explicitly stating its goal of pushing charters, instead beginning its work in Boston with a “lavishly choreographed rally” at Faneuil Hall. The rally did not mention charter schools at all.[13]

There were also Massachusetts-based groups under the Great Schools MA umbrella. Democrats for Education Reform (DFER) and the MA Charter Public School Association both poured in money. DFER’s first ominous sign occurred in the September 9th Democratic primary for a State Senate seat in Cambridge and Somerville. The race pitted anti-charter State Senator Pat Jehlen against pro-charter Cambridge City Councilor Leland Cheung. Cheung was closely connected with DFER, who funded his campaign. In response, MTA contributed a smaller amount to Jehlen’s campaign. Jehlen challenged DFER President Liam Kerr to a debate, stating that Kerr is her real opponent. Kerr agreed, and the election became a referendum on charter schools. Cheung ended up losing with just 20% of the vote to Jehlen’s 80%. DFER and the pro-charter lobby claimed that this vote was an outlier that did not represent the opinion of MA voters. Yet they made very similar statements after losing question 2; there is a clear trend and roadmap to oppose charters. These are not isolated losses, but rather a growing fundamental distrust of charter schools that will further manifest itself in the coming years.

Figure 3

The pro-charter campaign kept switching tactics, unable to settle on a central message that worked. Its chaotic messaging contrasted with the No campaign’s straightforward and concrete central message of district school funds being funneled to charters. That argument was reinforced by the hundreds of School Committees across MA that passed resolutions opposing question 2 because they knew firsthand how much money was lost to charters. As polls showed the yes side losing, the Yes side began to directly contradict the No side’s argument, “airing ads saying that charter schools would provide more money for public education.”[14] Another central pro-charter campaign argument was the waitlist, which changed during the campaign due to the MA Department of Elementary and Secondary Education (DESE) releasing a waitlist number that was artificially high. State Auditor Suzanne Bump said that “DESE had overstated the waitlist by an indeterminable amount by rolling over entries from prior years who may no longer be interested.”[15] Not everyone on a waitlist actually wants to go to that school; often students are placed on multiple waitlists so that parents retain a variety of options.[16] Normal public schools also have waiting lists, particularly in places like Boston. These waitlists are unable to “be as expansive as charter waitlists, since they’re only held till January” and do not roll over.[17] Since MA was ranked first in student achievement, and also because 96% of public school students in MA attend normal public schools, voters were generally positive toward the MA education system.[18] MA Parent Teacher Association and MA Municipal Association both officially opposed question 2.[19] These are well-respected and nonpartisan organizations that send a message of bipartisan opposition.

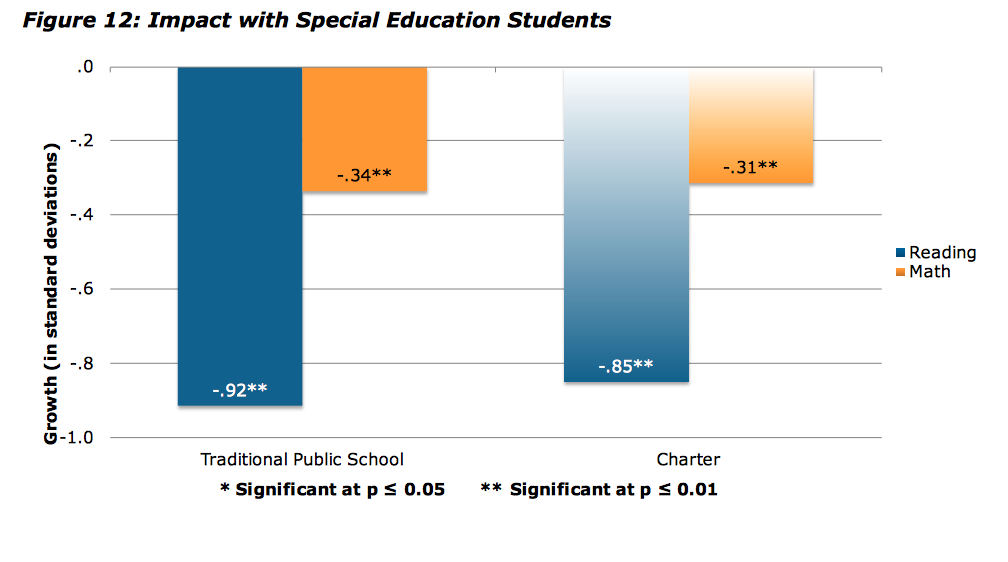

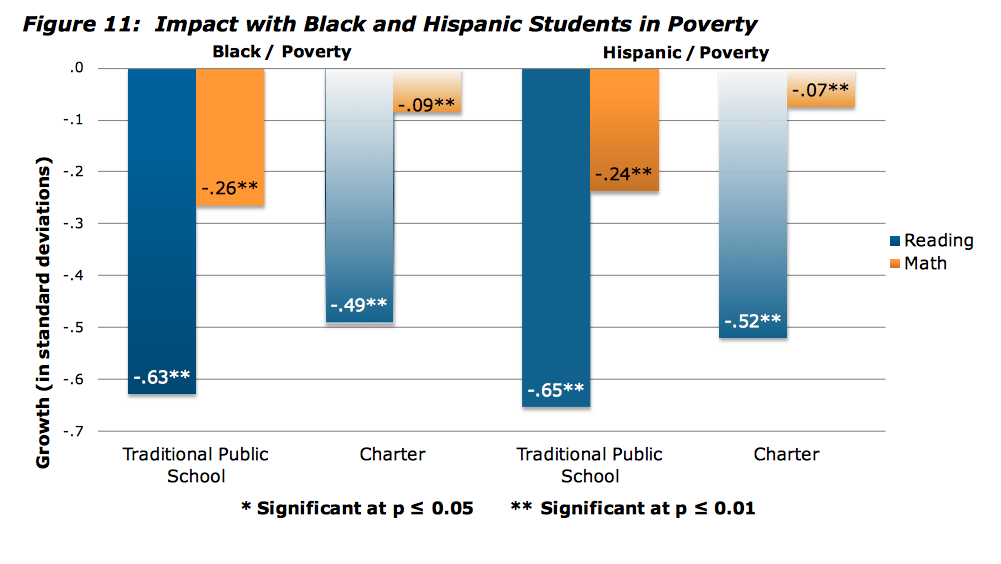

According to a Brookings study, charters in low-income and high-minority urban areas “have large, positive effects on educational outcomes” that are better than in district schools, and those effects are “particularly large for disadvantaged [and] SPED students” (see figures 1-3).[20] Another recent study showed that Boston charters that opened new schools after the cap was raised in 2010 “were able to maintain their strong results.”[21] On the other hand, students in rural and suburban charters “do the same or worse” than students in district schools.[22] The charter cap does not currently affect expansion of schools in suburban and rural areas, as they have not reached the cap.

The pro-charter side’s argument centered on ensuring that all students have access to a quality education. They argued that the referendum would modestly increase charters, and one ad even ended with “Yes on 2: for stronger public schools.”[23] Boston Mayor Marty Walsh, a traditional charter supporter and former member of the board of a Boston charter,[24] opposed the ballot question due to the “pace and scope” of charters that the referendum would allow for. He called the referendum “a looming death spiral aimed squarely at the most vulnerable children in our city.”[25] Sweeney, the Boston finance chief, agreed and thought that 12 new charters per year could “nearly eliminate the Boston Public Schools.”[26] If only 3 new charters were approved each year in Boston over the next decade, the Boston funds going to charters would increase from 5 to 20 percent. Charter advocates responded by saying that Boston has to “be responsible for getting its own fiscal house in order,” and that the city will have to close schools.[27] Nonpartisan city officials and financial watchdogs agreed with the No on 2’s argument that the increase in charters would drain dangerous amounts of money from public schools.

In Lowell, the cost of charters rose by 8.6 million over the past 9 years, but the state funding has stayed flat. Disproving another central Yes on 2 argument, “the charter school waitlist in Lowell…is dwarfed by the number of kids waiting to get into district schools.”[29] Lowell ended up voting against charters by 56.8 to 43.2.[30] The No side’s arguments spread far beyond education advocates to reach the average voter.

The No campaign “successfully connected charter school expansion to dark money and to a market-based ideological agenda,” revealing the Wall Street businessmen, conservatives, and New Yorkers that they argued were pouring money to dictate what’s best for Massachusetts. Since 2010, cities such as Boston, Fall River, and Lawrence have had an increase of 83% in charter spending but only 15% increase in state education aid. This results in money taken from other portions of the city budget, and the cities affected already have some of the highest poverty rates in the Commonwealth.[31] Due to overhead costs such as building maintenance and transportation, schools may “not be able to adjust to the loss of revenue” to charters.[32] Moody’s Investors Service agreed that passage of question 2 would be “credit negative” for the cities of Boston, Springfield, Lawrence, and Fall River.[33] The yes campaign responded by denying these concerns, stating that charters have “zero impact on district school finances.”[34] After question 2’s failure, Moody’s said that that result is “credit positive” for MA cities.[35]

The Yes side’s financial dominance allowed it to air an unprecedented amount of ads for a ballot campaign. One frequently aired ad consisted of Governor Baker saying, “Imagine if your kid was trapped in a failing school,” reaching for the emotions of white suburban voters to do what’s right for Black and Latino children in inner cities, whose images flash across the screen. Another ad said that it’s critical to raise the cap in order to remove what it claimed to be 37,000 students off charter waiting lists in MA. Great Schools MA’s TV ads “contain several themes from the pro-charter playbook,” and therefore the failure of this messaging means that it can also fail in future campaigns. For instance, the Boston Globe op-ed supporting question 2 emphasized students “languishing on waitlists.”[36] Good aspects of the traditional system “were generally portrayed as exceptions in a failing system,” which is false in Massachusetts’s top in the nation system. Since MA students rank first in the nation, voters are likely to oppose any drastic changes to the current system; the No campaign’s portrayal of the Yes side as extremist led many traditionally pro-charter politicians to take what they perceived to be the safer option and oppose question 2, thus shifting public opinion.

The most senior education officials in America backed the pro-charter narrative, with Secretary of Education John King, Arne Duncan, as well as Congressman Stephen Lynch, and Speaker DeLeo in MA. They joined together to attempt to unite the Democrats in an ad titled “Real Democrats are YES on Question 2.”[37] The No side included many politicians and officials who had traditionally been pro-charter. Mayor Walsh’s opposition to question 2 sent a clear message that opposing drastic expansion of charters does not mean one has to oppose charters themselves. Walsh opposed question 2 due to the deep budgetary implications it would have on Boston Public Schools. Mobilizing pro-charter politicians to oppose question 2 by depicting it as radical was a critical strategy; “more charter supporters recognize that Question 2 is the wrong solution” due to the dramatic increase of charters allowed as well as the lack of local control.[38]

In 2015, 412 million was taken from the 243 school districts and given to charters.[39] The No campaign successfully encouraged conversations with friends and neighbors about how much will be lost to charters if the number of charters dramatically increases. They emphasized the fact that 12 new charters per year would in 10 years nearly triple the number of MA charters. Furthermore, the dropping of the limit on the amount that a district could lose to charters could effectively eliminate public education in certain cities.[40]

A Skewed Budget: Financial Aspects of the Referendum Campaign

The Yes side spent $23.6 million to the No side’s $14.1 million,[41] making it the most expensive referendum campaign in MA history. The top 5 yes campaign donors were FES, followed by Alice Walton, the group Strong Economy for Growth, Jim Walton, and Michael Bloomberg. In contrast, the no campaign’s top donors were MTA, NEA, AFT, and AFL-CIO.[42] Local teacher unions in cities and towns affected by charters, such as Boston, Lowell, and Lawrence, also donated thousands.[43] Massachusetts corporations MassMutual Financial, State Street Bank, EMC Corporation, and Vertex Pharmaceuticals all contributed to Great Schools MA.[44] Wealthy out-of-state donors also poured money into the pro-charter effort; Arkansas residents and Walmart heirs Alice and Jim Walton donated $1.8 million while Michael Bloomberg gave $490,000.[45] FES poured 17 million to the Yes campaign but is not required to disclose donors and is registered in New York.[46] For “average voters…the outsized role being played by rich New Yorkers was utterly incomprehensible.”[47] $778,000 was also donated by bankers that manage MA pension funds to question 2.[48] The No campaign successfully crafted a narrative that conveyed the fact that wealthy, white out-of-state donors thought they knew what type of education was best for Massachusetts’ inner-city children. New England NAACP president and No on 2 campaign chair Juan Cofield said that “this is a truly unprecedented financial push by the charter industry to buy our election with untraceable money.”[49] The MA Charter Public School Association said that the out-of-state money from financial executives is essential to combating the financial power of teacher unions, despite the fact that the No side had nearly half the money of the Yes campaign.

The well-funded campaigns produced many TV ads and direct mail, which resulted in many more voters paying attention and thus more likely to make an informed choice. Opposition to charters became more than a niche issue. Undecided voters realized that there was “something fishy” about the Yes on 2 campaign’s seemingly constant back-to-back TV ads. This suspicion was confounded by additional deceptive tactics; for instance, one of the five pro-charter campaign committees was called, “Advancing Obama’s Legacy on Charter Schools Ballot Committee,” tying the yes campaign to Obama despite the fact that he did not weigh in on either side.[50]

Leading the Opposition: The Role of Teacher Unions in the Campaign

For the past few decades, teacher unions had been on the defensive about charters. But throughout the campaign, unions–particularly the MTA under Barbara Madeloni–were on the offensive. It was reported that $778,000 was donated to Great Schools MA by “executives from eight financial firms that hold management contracts with the state pension fund,” which is led by strong charter-supporter and popular Republican Governor Charlie Baker.[51] MTA and AFT-MA filed with the SEC to call for federal and state investigation into hedge fund managers’ donations to the yes campaign. Those executives cannot donate to Baker’s campaign due to campaign finance regulations, but they are able to donate to the pro-charter campaign and thus gain favor with him. Campaign finance experts said that this is a way for executives to “legally circumvent pay-to-play rules.”[52] Madeloni was on offense in a statement, saying, “it is appalling that ads starring [Baker] are being financed by donations from Wall Street fund managers who have an interest in currying favor with the administration.”[53] Baker called it a “distraction.”[54] While the investigation did not go anywhere, it obtained negative media coverage for the pro-charter campaign and contributed to the public perception of the Yes side being funded by wealthy donors disconnected from Massachusetts communities.

NEA President Lily Garcia said, “This is really important for us.” NEA’s 3 million members make it the largest union in America, and thus its backing carries substantial weight. Politico wrote before the election that the failure of question 2 would be “a significant symbolic coup for teachers unions.”[55] Failure of question 2 would also “deter other states from considering [charter] expansions amid signs the anti-charter side is gaining momentum.” The union’s first victory came in the form of the Democratic Party platform at the 2016 convention, which, at the personal request from AFT President Randi Weingarten, was amended to be more anti-charter than ever.[56] The grassroots no on 2 campaign was driven by local teacher unions, which are present in every district and are run and staffed almost entirely by teachers in that district. For instance, Belmont Education Association (BEA) handed out anti-charter flyers containing the BEA logo at major Belmont events. Parents’ “conversation with local teachers played a central role in building opposition.” One voter said that teachers in her town of Brookline “are the ones who really made up my mind.”[57] A variety of other unions, from AFSCME to CWA, joined the teacher unions to form a broad labor coalition under the SOPS umbrella, expanding the grassroots reach of the anti-charter effort.

The pro-charter side claimed that teachers were pressured by the union to oppose question 2. One teacher said that on the first day of her job, all teachers met in the auditorium. The local union president then gave a speech about the No campaign, and slips of paper were passed out to sign up for the No campaign.[58] Others argue that it’s a “lazy script” to simply attribute defeat of question 2 to teacher unions. In reality, “the vote…represents a political realignment” on the charter issue due to progressives firmly united against them.[59] People on the ground understood this, though those out-of-state were disconnected and thus “stunned when Elizabeth Warren announced she was No on 2,” failing to understand the degree of the realignment.

From the Bottom Up: Grassroots Organizing and the Leadup to the Question 2 Vote

Save Our Public Schools (SOPS) was the No campaign’s umbrella organization, which itself is a more direct branding than the vague name Great Schools MA. Organizations under the umbrella included MA Teachers Association, AFT Massachusetts, New England NAACP, Citizens for Public Schools, MA AFL-CIO, and other community groups.[60] The role of unions as running the No campaign, a narrative promulgated by the Yes campaign and mainstream media, is “exaggerated.” Teacher unions “were only one component of a broad-based and diverse No coalition.” Unpaid volunteers “did a staggering amount of work.” For instance, parents in Boston alone were organized into the group Quality Education for Every Student, which ran “highly organized” canvasses and phone banks consistently throughout the summer and through election day.[61] Anti-charter volunteers contacted 378,000 households in Boston while the Yes campaign contacted 150,000 in Greater Boston.[62] Average people took it upon themselves to help out the No campaign; for instance, parents made videos that went viral on social media, and volunteers “turned their homes into makeshift call centers” to phone bank. Many students also contributed by canvassing, phone banking, and using the infrastructure built during their 2016 budget walkout.[63] “The coalition extended well beyond teacher unions”[64] to include civil rights groups and social justice organizations. All of these groups “fanned out across the state every weekend” to spread the word. The No campaign canvassed 1.5 million voters–a stunning figure for a referendum campaign–and the final tally was 2 million votes against the measure. Therefore grassroots campaigning truly did make a large difference, and the victory indicates “the potential of substantial pushback against the corporate agenda from coordinated grassroots organizing.”[65]

The Yes campaign had far fewer people canvassing, phone banking, and spreading the word via social media.[66] Their “grassroots” field operation was actually made up almost entirely of people who were paid to knock doors, make phone calls, hold signs, and poll watch. Many were not even from MA. The campaign attempted to portray an image of being driven by support from low-income, inner-city people of color. A few parents of color, whose children went to Boston charter schools, spoke at highly choreographed Yes on 2 rallies to portray an image of African-American support. In the end, it was impossible to create support where it didn’t exist. The rallies and support for the No on 2 campaign were less scripted and more genuine.

215 School Committees passed resolutions opposing question 2, highlighting the loss of funds to their district schools and thus reinforcing the No campaign’s central argument. They also emphasized the lack of ELL and SPED resources in charters, which leave district schools to take on the burden of financing those more expensive students. Because the resolutions were passed consistently from the spring through the November election, they provided the No campaign with a “strong sense of momentum” that was publicized in order to control the media narrative.[67] Each local school board resolution resulted in media coverage in each city and town, and allowed local canvassers and phone bankers to gain traction. Use of school boards could be an impactful strategy in the success of future campaigns.

Racial Aspects and the African-American Mobilization Against Question 2

Black and Latino parents organized in their communities through groups such as the NAACP, Black Educators Alliance of MA, and Union of Minority Neighborhoods.[68] NAACP not only endorsed No on 2 but was a direct member of the campaign committee, and Juan Cofield–NAACP New England President and SOPS chair–was the public face of the No campaign. This was critical not only in turning a substantial constituency against charters, but also in showing that the Yes campaign’s narrative of voting yes to support inner-cities is backward because inner-city voters overwhelmingly opposed question 2. A few months before the vote, the NAACP convention voted for a moratorium on charters expansion “until they adopt the same level of oversight, civil rights protections, and transparency as public schools.”[69]

Some black pro-charter organizations opposed the NAACP position, such as the Black Alliance for Educational Options and African-American Boston newspaper Bay State Banner.[70] The Yes campaign used tactics with underlying racial motives; for instance, they sent a mailing covered by a picture of President Obama, with text that said “preserve Obama’s education legacy,” yet Obama was never involved in either side. FES created a group called Unify Boston, which spent months getting signatures from parents of color who wanted “great neighborhood schools.” Yet when the leaders told the signature gatherers “that the actual goal of the campaign was to lift the charter cap, a revolt broke out.” A former organizer remarked, “It’s like they think people of color are stupid.”[71]

Black politicians such as Boston City Councilor Tito Jackson and Boston NAACP President Michael Curry played a prominent role in mobilizing their community against question 2. Both represented the No side in debates, attended rallies, and served as “go-to persons for Boston newspaper articles on the campaign.”[72] They showed the depth of No campaign’s support in the black community, rather than the artificial image of support that the Yes campaign attempted to portray.

In areas of Boston like Mattapan, with some of “the lowest performing schools in the state, opposition to Question 2 ran deep,”[73] with many people repulsed by outsiders believing they knew best without actually being on the ground in the community. Boston NAACP president Michael Curry said that “communities of color spoke loudly.”[74] Some of the most emphasized pro-charter arguments highlighted the need to support students of color in failing schools. For instance, one journalist wrote a piece titled, “It’s Heartbreaking’: Boston Parents Ask Why Their Wealthy Neighbors Are Fighting Charter Schools.”[75] This piece tried to portray charters as supported by people of color who live in areas with the highest concentration of charters. But the overwhelming 2 to 1 opposition in those areas showed the opposite; the landslide against charters in inner-city Boston is even a larger margin than the statewide result.[76] Civil rights leaders “say families of color yearn for something deeper [than charters]: A plan to improve the quality of education…so they don’t need alternatives.”[77]

A New Era: Democratic Party Solidarity Against Question 2

Democrats and Republicans initially supported question 2 in similar numbers.[78] In the final vote, Democrats opposed it overwhelmingly. At the June 4th, 2016 MA Democratic State Convention, an event I attended, “Save Our Public Schools” signs abounded despite the fact that the question had not yet even been certified for the ballot. Signatures were submitted by the pro-charter campaign on June 22nd, and the question was certified on July 6th.[79] Pro-charter forces also made a massive push for Democratic delegates and activists. DFER, for instance, was the only outside group to send an official mailing to delegates prior to the state convention. That mailing was an invitation to a DFER breakfast for delegates, which had elaborate food and was attended by pro-charter state legislators. SOPS did not have a breakfast, but it was clear at the convention that they had the people. Numerous SOPS tables appeared throughout the convention hall, and anti-charter stickers were a near-constant sight on delegates while hardly any pro-charter stickers could be spotted. DFER also paid for multiple breakfasts–which cost around $5000 each–at the Democratic National Convention,[80] attempting to portray an image of support for charters in MA.

The No on 2 campaign “tapped into genuinely viral energy.” This spurred the MA Democratic Party to officially oppose question 2, which likely would not have happened without the enormous grassroots mobilization. This stance against charters is at odds with some Democratic legislators, including Speaker DeLeo.[81] Bernie Sanders and Elizabeth Warren both endorsed the anti-charter campaign. Warren echoed the central argument of the anti-charter campaign, saying that more charters would damage the education of “students in districts with tight budgets where every dime matters.” She emphasized that 400 million was taken from public schools to charters, resulting in cuts to district schools including “in arts, technology, AP classes, preschool, bus service, and more.”[82] In a blue state like MA, Democratic unity contributed greatly to the No campaign’s landslide victory.

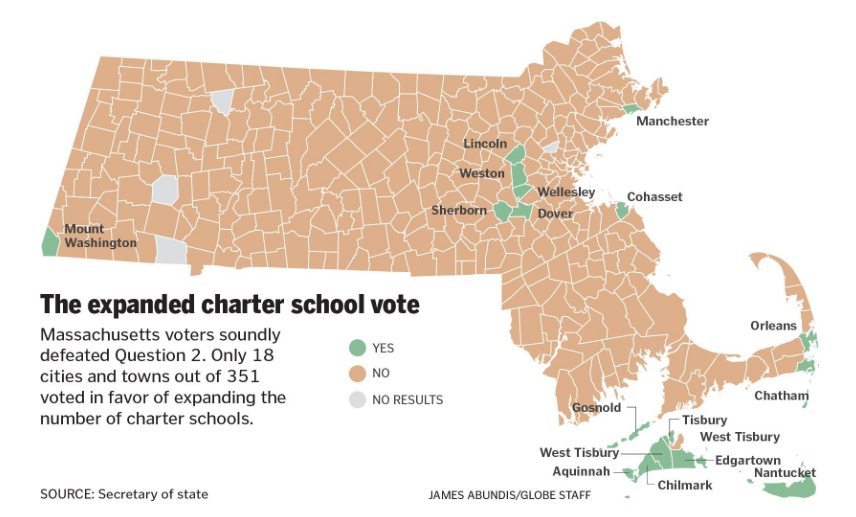

Crossing the Partisan Divide to Oppose Charters: Geographic Trends in the Election Results

Figure 4

The anti-charter effort was victorious in almost every town in Massachusetts. The few towns that voted yes were also some of the wealthiest in Massachusetts. Weston, easily the wealthiest town with median household income of $201,200,[83] voted 60-40 in support of charter schools, the second highest margin in the state (the highest was 61-39 in Aquinnah, a tiny affluent community on Martha’s Vineyard).[84] Dover, the second wealthiest town, voted 58.7 to 41.3 for charters, the third highest pro-charter margin in the state. Sherborn, with the fifth highest pro-charter margin, is also the fifth wealthiest town. There is a clear correlation between the wealthiest towns and the highest pro-charter margins. The exclusive affluent communities of Nantucket and Martha’s Vineyard supported charters. On Martha’s Vineyard, wealthy white Edgartown and Chilmark voted yes, while the heavily African-American community of Oak Bluffs voted no, signaling that pro-charter support among the wealthiest Bay Staters was limited to whites.

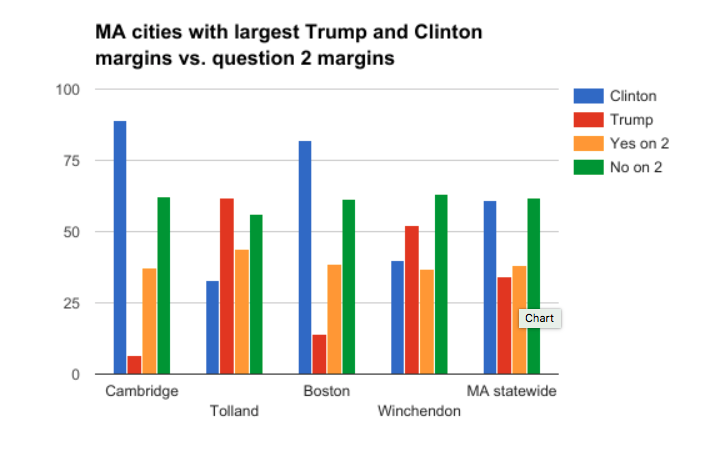

Figure 5

Towns that voted for Trump by high margins also voted against charters by margins similar to those in Boston, Worcester, and other liberal cities. For instance, Tolland had the highest margin for Trump and Cambridge had the highest margin for Clinton, but their charter margin was remarkably similar. This implies that Trump-DeVos education policies are not popular with his white working class base, and therefore it’s critical for public education advocates to mobilize that group in order to most effectively resist. The No campaign’s tactic of grassroots outreach in all areas of the Commonwealth succeeded even in white, working-class, Trump supporting areas and therefore a similar anti-charter strategy can be successfully applied across the Midwest and throughout the country. The statewide trend was replicated along wealth lines in Boston itself. The largest anti-charter margin occurred in the predominantly low-income and African-American area of Roxbury while the highest margin in support of charters occurred in the wealthy and white Back Bay.[85] The coalescence of the black community around the anti-charter campaign was reflected in the inner city vote total, with Roxbury, Mattapan, and Dorchester all voting around two to one against question 2. All cities and towns with a large number of charter schools voted against question 2. In fact, no town that voted for charters has a single charter school.

A Model for the Nation: Applying Lessons from the Massachusetts Anti-Charter Campaign to Future Public Education Advocacy

The day after the vote, the Boston Globe headline read, “Crushing defeat leaves charter-school movement in limbo.”[86] This “exceeded the worst case scenario” of charter supporters. One researcher at a pro-charter thinktank acknowledged that the anti-charter side came out ahead on every argument.[87] The No side gained the upper hand because it convinced undecided voters while the Yes side hardly expanded its base. DFER was “quick to issue statements of “we’ll be back – talking-pointed bravado…that conveyed nothing so much as a failure to recognize the magnitude of their loss.”[88] Charter advocates say not to read into the vote. But according to the National Education Policy Center, “the MA campaign suggests that the neoliberal, pro-charter narrative” is ending.[89]