Ambassador Ido Aharoni, Consul General of Israel in New York recently visited Yale and stopped by the library to view several of the recently acquired illuminated manuscripts that were in the Judaic Studies Librarian’s office. He has been a member of Israel’s Foreign Service since 1991. In the photo Judaic Librarian, Nanette Stahl, is showing Ambassador Aharoni a new purchase.

Ambassador Ido Aharoni, Consul General of Israel in New York recently visited Yale and stopped by the library to view several of the recently acquired illuminated manuscripts that were in the Judaic Studies Librarian’s office. He has been a member of Israel’s Foreign Service since 1991. In the photo Judaic Librarian, Nanette Stahl, is showing Ambassador Aharoni a new purchase.

David Moss Visit

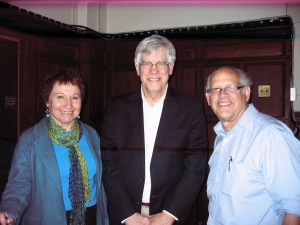

April 9–we had the good fortune to have the noted Israeli artist and scholar, David Moss, speak at the library about his work with the aid of a magnificent slide presentation. The range of his work is most impressive. In addition to his illuminated manuscripts and his specially commissioned Passover haggadah, he designed a shtender, a high study table which was traditionally used by Talmud scholars when they studied while standing up. He also works on artistic maps that present places in Israel that are close to his heart, a glass book which contains Rabbi Nahman of Bratislav’s prayer for peace, and other imaginative and beautiful books and artifacts that relate to Jewish life and tradition. The photo shows David (on the right) with Steven D. Fraade, the Mark Tapper Professor of the History of Judaism and Chair of the Program in Judaic Studies and Nanette Stahl, Librarian for Judaic Studies.

Restarting the Blog

We are happy to announce that after a long hiatus, the Yale University Library Judaica blog will begin active posting again. We’ve had some changes in the past two years, and we’re excited to share some of our new acquisitions. Please visit our website (http://www.library.yale.edu/judaica/) for access to our digitized exhibits before they are featured on the blog. In the mean time, here are some current photos of the staff:

Acquisitions Assistant Julie Cohen, Judaica Curator Nanette Stahl, and Archive Assistant Hana Rudnick

New Online Exhibit: Mikail Magaril, Mestechko

![]() Artist Mikhail Magaril has taken Leo Tolstoy’s text and adapted it to images from the Jewish shtetls that once existed in Eastern Europe. Click here to visit exhibit.

Artist Mikhail Magaril has taken Leo Tolstoy’s text and adapted it to images from the Jewish shtetls that once existed in Eastern Europe. Click here to visit exhibit.

Yiddish Book Collection of the Russian Avant-Garde

The Yiddish Book Collection of the Russian Avant-Garde contains books published between the years 1912-1928 by many of the movement’s best known artists. The items here represent only a portion of Yale’s holdings in Yiddish literature. The Beinecke, in collaboration with the Yale University library Judaica Collection, continues to digitize and make Yiddish books available online.

With the Russian Revolution of 1917, prohibitions on Yiddish printing imposed by the Czarist regime were lifted. Thus, the early post-revolutionary period saw a major flourishing of Yiddish books and journals. The new freedoms also enabled the development of a new and radically modern art by the Russian avant-garde. Artists such as Mark Chagall, Joseph Chaikov, Issachar Ber Ryback, El (Eliezer) Lisitzsky and others found in the freewheeling artistic climate of those years an opportunity Jews had never enjoyed before in Russia: an opportunity to express themselves as both Modernists and as Jews. Their art often focused on the small towns of Russia and Ukraine where most of them had originated. Their depiction of that milieu, however, was new and different.

Jewish art in the early post-revolutionary years emerged with the creation of a secular, socialist culture and was especially cultivated by the Kultur-Lige, the Jewish social and cultural organizations of the 1920s and 1930s. One of the founders of the first Kultur-Lige in Kiev in 1918 was Joseph Chaikov, a painter and sculptor whose books are represented in the Beinecke’s collection. The Kultur-Lige supported education for children and adults in Jewish literature, the theater and the arts. The organization sponsored art exhibitions and art classes and also published books written by the Yiddish language’s most accomplished authors and poets and illustrated by artists who in time became trail blazers in modernist circles.

This brief flowering of Yiddish secular culture in Russia came to an end in the 1920s. As the power of the Soviet state grew under Stalin, official culture became hostile to the experimental art that the revolution had at first facilitated and even encouraged. Many artists left for Berlin, Paris and other intellectual centers. Those that remained, like El Lisitzky, ceased creating art with Jewish themes and focused their work on furthering the aims of Communism. Tragically, many of them perished in Stalin’s murderous purges.

The Artists

Eliezer Lisitzky (1890–1941), better known as El Lisitzky, was a Russian Jewish artist, designer, photographer, teacher, typographer, and architect. He was one of the most important figures of the Russian avant-garde, helping develop Suprematism with his friend and mentor, Kazimir Malevich. He began his career illustrating Yiddish children’s books in an effort to promote Jewish culture. In 1921, he became the Russian cultural ambassador in Weimar Germany, working with and influencing important figures of the Bauhaus movement. He brought significant innovation and change to the fields of typography, exhibition design, photomontage, and book design, producing critically respected works and winning international acclaim. However, as he grew more involved with creating art work for the Soviet state, he ceased creating art with Jewish themes. Among the best known Yiddish books illustrated by the artist is Sikhes Hulin by the writer and poet Moshe Broderzon and Yingel Tsingle Khvat, a children’s book of poetry by Mani Leyb. Both works have been completely digitized and can be found in the Digital Collection of the Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library.

Joseph Chaikov (1888-1979) was a Russian sculptor, graphic artist, teacher, and art critic. Born in Kiev, Chaikov studied in Paris from 1910 to 1913. Returning to Russia in 1914, he became active in Jewish art circles and in 1918 was one of the founders of the Kultur-Lige in Kiev. Though primarily known as a sculptor, in his early career, he also illustrated Yiddish books, many of them children’s books. In 1921 his Yiddish book, Skulpturwas published. In it, the artist formulated an avant-garde approach to sculpture and its place in a new Jewish art. It too is in the Beinecke collection.

Another of the great artists from this remarkable period in Yiddish cultural history is Issachar Ber Ryback. Together with Lisistzky, he traveled as a young man in the Russian countryside studying Jewish folk life and art. Their findings made a deep impression on both men as artists and as Jews and folk art remained an abiding influence on their work. One of Ryback’s better known works is Shtetl, Mayn Khoyever heym; a gedenknish (Shtetl, My destroyed home; A Remembrance), Berlin, 1922. In this book, also in the Beinecke collection, the artist depicts scenes of Jewish life in his shtetl (village) in Ukraine before it was destroyed in the pogroms which followed the end of World War I. Indeed, Shtetl is an elegy to that world. Click here to see an online exhibit of Ryback’s Portrait of Shtetl Life.

David Hofstein’s book of poems, Troyer (Tears), illustrated by Mark Chagall also mourns the victims of the pogroms. It was published by the Kultur-Lige in Kiev in 1922. Chagall’s art in this book is stark and minimalist in keeping with the grim subject of the poetry. Chagall was a leading force in the new emerging Yiddish secular art and many of the young modernist artists of the time came to study and paint with him in Vitebsk, his hometown. Lisistzky and Ryback were among them. Chagall, however, parted ways with them when their artistic styles and goals diverged. Chagall moved to Moscow in 1920 where he became involved with the newly created and innovative Moscow Yiddish Theater.

These books are part of the General Modern Collection at the Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library at Yale University. Search the Beinecke’s Digital Collection by author name to find more images.